Within the Bolivia 2020 Pre-Expedition developed in February 2020 by the Akakor Geographical Exploring team under the direction of Lorenzo Epis, the imposing Salar de Uyuni and surrounding areas in the Department of Potosí in Bolivia, were visited, thus elaborating on the preliminary study of some archaeological sites. The present article addresses one of these fascinating places in an attempt to understand if the ancient Andeans had a complex understanding of astronomy and an ancient Andean calendar.

Exploring the Salar de Uyuni

The Salar de Uyuni , or Uyuni Salt Flats, in the Andean highlands is located around 3,650 meters (11,975 ft) above sea level. It is the largest continuous salt desert on the globe, with a surface that that covers 10,582 km² (4,086 mi²).

In the past, the Salar de Uyuni salt flat was known as the Salar of Tunupa . This name is significant due to the fact that, to the south of the Department of Oruro, in the Municipality of Salinas de Garci Mendoza and bordering the Salar de Uyuni, the volcano of Tunupa is located. In legend, this is the residence and altar of the deity of thunder and the lightning, Tunupa. Variations of Tunupa are Tuapaca or Taguapaca and its Castilianization or Spanish version is Tarapacá. These are all evocations of Tauapácac Ticci Viracocha, the God of the Staffs .

Now, from a geological perspective, around 40,000 years ago this area sheltered Lake Minchinnota, and then 11,000 years ago Lake Tauca. It is during this period that a humid climatic phase allowed these lakes to reach a height of around 100 m (328 ft) above the current level. However, a dry and warm period generated a significant reduction in the surface and volume of these lakes, consequently forming the salt flats of Uyuni and Coipasa, as well as the current lagoons. The Poopó and Uru-Uru lakes are also residues of these large lakes.

The vista of the Uyuni salt flat is impressive. In the central part of the salt flat, the Island of Incahuasi – the Casa del Inca or “House of the Inca” in Quechua – is located. It covers an area of 0.24 km² (0.09 mi²) and is home to numerous giant cactuses known as Echinopsis atacamensis which can reach 10 m (32.8 ft) in height. The highest point of Incahuasi is 3822 m (12,539 ft above sea level).

Left: View across the Salar de Uyuni to Tunupa volcano from the Island of Incahuasi. Right: A natural bridge in Incahuasi. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

Silent Vestiges of the Ancient Chullpas Culture

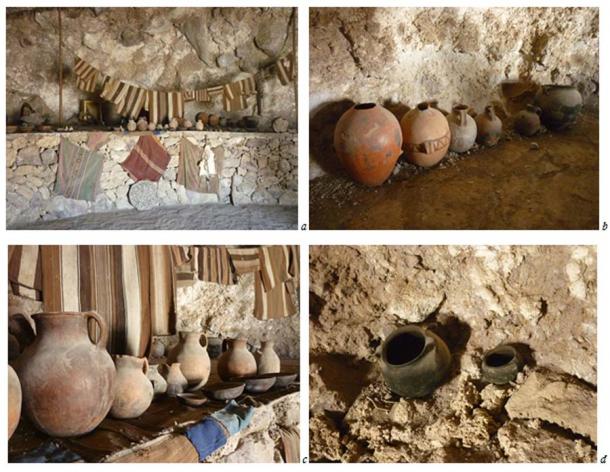

In the Tanilvinto area, located in the geographical region of the Salar de Uyuni there are vestiges in a grotto of the remote culture of the Chullpas whose closest descendants today are the Chipayas. The vestiges correspond to four partially mummified individuals, three adults and one infant, and some magical-religious objects. The burial goods of these individuals is minimal: It is limited to the first two “mummies” and consists of two vessels in each.

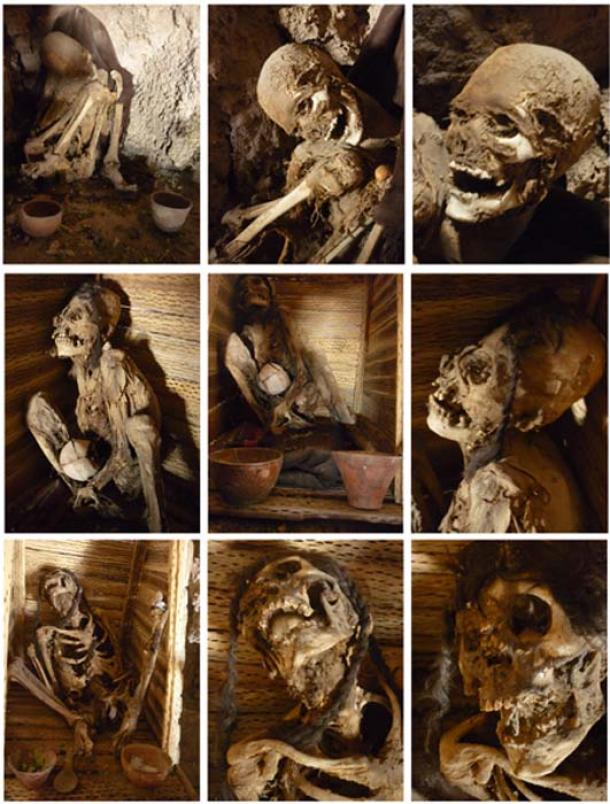

Originally there were two adults and the infant in the grotto, while the fourth “mummy” was about 200 meters (656 ft) “to the right” outside the grotto. These so-called mummies have elongated skulls. The female shelters the infant next to herself.

Tanilvinto mummy with elongated skull, embracing the child. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

It is worth mentioning that the contemporary rituality of the people of the area has meant the placing in the grotto of further vessels, with offerings such as coca leaves ( Erythroxylum coca ), cigarettes and alcohol, along with Aguayos textiles with Andean ritual symbolism. Likewise, the ancestral Ko’a rite – in honor of the earth goddess, Pachamama – a kind of propitiatory offering/sacrifice, is celebrated on August 1st every year.

The vestiges. a) Overview of the grotto where the “mummies” are located. b) c) d) Modern vases, plates and Aguayos textiles that accompany the mummies. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

Searching for the Lost Origins of an Ancient Andean Calendar

A fundamental element of ancestral rituality and its projection in the contemporary community is the preservation of an astronomical calendrical system of sowing and harvesting , an object that was kept by Mrs. Eleuteria Quispe Barco and inherited by her descendants. Unfortunately, the origin of this Andean calendar system has been lost and its function and the reason for its peculiar design are also unknown.

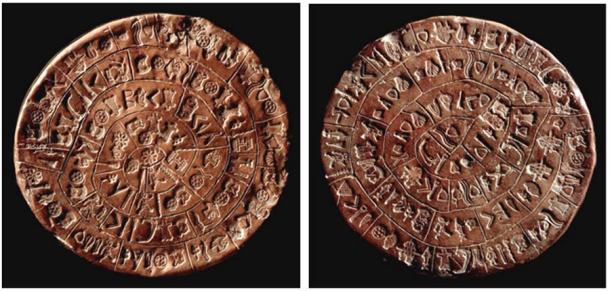

This Andean calendar is a spiral symbol that has 316 pieces carved from bones and ceramics, some of which were detached and they were replaced by ceramic or glass fragments of European and colonial origin. The Andean calendar was made of fired clay and has a diameter of 54.5 cm (1.78 ft). Its thickness is 7.5 cm (2.95 in).

Tanilvinto’s fantastic calendrical system. It is a fired clay disc that reaches a diameter of 54.5 cm and that presents a spiral symbol whose design is made up of numerous pieces, some of them with rune-like symbols and others of unknown meaning. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

The fragmentary information that we have was communicated to us by Mr. Iván Quispe, grandson of Mrs. Quispe Barco who died in 2013. Mr. Quispe himself has stated the existence of other “mummies” in the surrounding mountains. In addition, there are some petroglyphs and “small hands” stamped in the area.

Near this site there is another grotto called the Cueva del Infierno (meaning “Grotto of Hell”), a beautiful and surprising coral formation inhabited by “spirits” and by the “Devil” as the grandparents – los abuelos – of the area expressed due to the “underground noises” that were heard inside.

Who were the individuals with elongated skulls that today rest in the grotto? What culture do they belong to? What is their age? Where did they come from? What were the characteristics of their society? What were their cosmogonic, religious, and political views? What was their language? Was there any kind of relationship with the indigenous (brachycephalic) populations? What was their destiny?

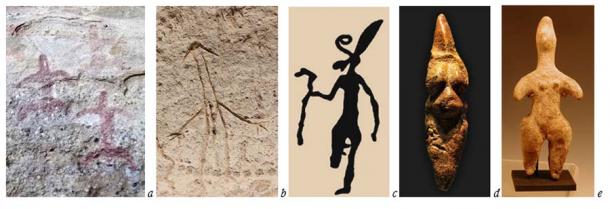

The questions are many. For now, it is only possible to verify the existence of this extraordinary site and an approach to the remains that are found there, especially the “mummies” with long skulls. In this respect, in relation to the nature of these individuals, a key to that remote past is given by the manifestations of art.

Art as a Source of History

Many of the representations of the Hówen or “spirits” that descended from the stars in the creation tradition of the Háin of the Selk’nam of Tierra del Fuego – in the extreme south of Chile – present conical headdresses. Something similar occurs in the Mesoamerican cultures with the Kukulkanes or the “Mighty Ones of Heaven”, of Quetzalcóatl or the “Feathered Serpent,” the god of Venus, as well as the four powerful B’aah kab , those who “hold the pillars of the heaven.” All of them arrived from the sky.

Likewise, this characteristic is observed in the Olmec, Colima, Chupicuaro, Jama-Coaque sculptural representations and also in some magical-religious representations of the Arikara-Tanish, Hopis and Tlingit, among others. The phenomenon is certainly not exclusive to the Americas as German-Scandinavian folklore also has references to celestial beings such as Wotan (Odin), Týr (Tiwaz) and Thor (Þunraz). Meanwhile, Egyptian myths refer to Horus, Nut, and Hathor as deities of heaven. The Indus Valley civilization accounts for Dyaus Pita, Indra, and Aditi.

Undoubtedly, the list of heaven gods worldwide is extensive. Now, the representation of the gods has a common factor: They are anthropomorphic figures with the particular characteristic of a conical headdress, bonnet or cap. Why? What was its meaning? How can we explain and understand the undeniable similarity in all these cultures and civilizations that did not have contact with each other?

This is when the information from a Mesoamerican source that was able to evade the fire of the implacable Inquisition in Mexico provides the fundamental key to understand the meaning of this symbolic outfit: It is the Códice Ramírez.

Relación del origen de los indios que habitan en la Nueva España según sus historias (“Codex Ramírez: A Relation of the Origin of the Indians That Live in New Spain According to Their Accounts) ( Ca. 1585), known too as the Manuscript Tovar, was written by the Jesuit Juan de Tovar ( Ca. 1546 – Ca. 1626) the son of the conqueror Juan de Tovar and a mestizo woman, descendant of the conqueror Diego de Colio. For these reasons, De Tovar spoke the Nahuatl, Otomi and Mazahua languages and was knowledgeable not only of the general cultural fields of the natives but also of their magical-religious and esoteric traditions.

Juan de Tovar described one of the most important Mesoamerican deities, the Kukulkán Quetzalcóatl – “Quetzalcóatl, particular god of the Chulula” who had his main temple in the Cholula pyramid – with a shield, a cap, a curved knife and the Ocelocopilli.

Quetzalcóatl with the Ocelocopilli conical headdress, symbol of Venus. He is a winged god! Watercolor on 21 x 15.2 cm paper. It is the illustration of the verse from page 132 of the Codex Ramírez. (John Carter Brown Library).

The Ocelocopilli is a conical headdress made of jaguar skin and decorated with jewels and corresponds to a symbol of the star of Venus. On Venus live the gods Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli and Xólotl – a region called Ilhuicatl-Huitztlán (“Place of the Path of the Sun”) – one of the Thirteen Heavens or Ilhuicatl Iohtlatoquiliz of the Aztec cosmogony.

The association of the conical headdress as an emblem of the gods of the firmament and the elongated skulls, is decisive. And these skulls are precisely the evidence that shows the reality of the iconographic representations of the gods. It is the iconographic-symbolic key – not arbitrary or interpretable but the expression of an idea (ἰδέα, idea = “form”) – that is practically verified on a global scale about the gods and their primordial civilization.

Paleolithic representations of the gods. Note the “elongated” heads as a common feature. a) A group of petroglyphs in Tierra del Fuego, in Chile, with the representation of the Hówen or “spirits” that descended from the stars of the Selk’nam tradition. b) Anthropomorphic petroglyph in Lava Beds, California, in the United States. c) Petroglyph at Wādi el Qash in Egypt. d) The Venus de Savignano, found in the homonymous place in Emilia-Romagna, Italy. e) A “goddess” of the Amlash culture, in Iran. (Author provided)

The conical headdress known as Ocelocopilli in Mesoamerica is a symbol of the star of Venus. a) The Hówen K’terrnen, the ‘Man of Light’ of the esoteric tradition of the selk’nam Háin of Tierra del Fuego in Chile (Photograph by Martin Gusinde, 1923). b) A Huasteca-Aztec representation of Quetzalcóatl as Lord of Venus, with the Ocelocopilli (Museo Nacional de Antropología de Ciudad de México). c) Effigy of Brahma from Tamil Nadu, India (British Museum). d) The god Aton in his temple at Karnak (Egyptian Museum of Cairo). e) Representation of Wotan/Odin with a conical helmet. (Statens Historika Museum in Stockholm)

Into the Unknown Past

In order to understand the fascinating past of this part of Bolivia, it is important to understand its past environment. What were the bioclimatic characteristics? What were the rainfall rates? What have been the climatic variations in the area? What flora and fauna were there? In relation to the occupational factors of the area: When did the first inhabitants arrive? What are the oldest vestiges? Has there been cultural overlap? What characteristics did this place have in order to become the habitat of this cultural substrate?

The “ mummies” have the characteristic elongated cranial feature. This particularity is a direct sign of the gods, reaching all the way from Tierra del Fuego to Alaska. This cultural substratum is remote and predates the indigenous population.

The “mummies” in the grotto. Its location, from left to right, in the first, second and third rows, respectively. a) The first “mummy”, in a fetal position. b) A woman and her infant. Notice the braid that still is preserved. c) The third “mummy”, also with braids. All have been accompanied with contemporary propitiatory elements such as coca leaves, cigarettes and alcohol. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

Cosmic symbology. Even when it comes to contemporary objects in the grotto, the powerful aboriginal symbolism is preserved in them: It is the eight-pointed star, emblem of Venus or Ch’aska Quyllur – Paqari Quyllur – one of the tutelary cosmic bodies next to the Sun and Moon in Andean cosmogonic tradition. Left: Vase with the design of an eight-petal flower-star, from the vertical plane. Right: Detail of an Aguayo, with the symbol of Venus. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

The Gods and the Calendrical System

It is a unique piece. Enigmatically fascinating. As has been noted, its origin, function and the reason for its design is unknown. The only information about this extraordinary object is its calendrical nature of sowing and harvesting, a fact that implies seasonal and astronomical observation and the knowledge of approximate and recommended dates for planting, transplanting and harvesting horticultural species and other plants in the annual cycle that we seek to cultivate. The direction of the spiral is left-handed, that is to say, its direction is oriented counterclockwise .

Tanilvinto’s fantastic calendrical system. It is a fired clay disc that reaches a diameter of 54.5 cm and that presents a spiral symbol whose design is made up of numerous pieces, some of them with rune-like symbols and others of unknown meaning. Where was its origin? What was its function? How was its knowledge transmitted? (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

The relationship of the spiral symbol with the gods in a set of blocks with petroglyphs near Monte Patria, in the Coquimbo Region, in Chile. Left: A spiral symbol. Right: A Viracocha, with a great headdress (Rafael Videla Eissmann)  Representations of spirals in temples of Babylon, India and Cuzco, respectively. The spiral symbol is associated with the forces of light in motion. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

Representations of spirals in temples of Babylon, India and Cuzco, respectively. The spiral symbol is associated with the forces of light in motion. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

The Phaestus Disc, made of fired clay with inscriptions on both sides and dated to the late Bronze Age. It was discovered on July 15, 1908 by archaeologist Luigi Pernier in the excavation of the Minoan Palace of Festos, near Hagia Tríada, in Crete. (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

The Puquíos. The fascinating spiral constructions known as Puquíos of the ancient Nazcas, in southern Peru. These constructions formed a sophisticated wind-powered irrigation system. What was the origin of this pre-Hispanic technology? (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

Left: Messier 94 spiral galaxy in the Canes Venatici constellation –at a distance of 16 million light years– (Image: ESA/NASA). Right: Tanilvinto’s calendrical system. Is it a very distant memory of the gods? (Rafael Videla Eissmann)

What was the origin of the knowledge embodied in the ancient Andean calendar? What is its age? What was the original model? What was its primary function and meaning? Was it a solar, lunar, or a lunisolar calendar? What was the meaning and function of the pieces that make up the design? How was the knowledge of the calendrical system transmitted? Is there another similar piece? Is this calendar an inheritance from the ancient gods?!

Along with the elongated skulls, the fundamental key is provided by the presence of runic symbols, or rune-like symbols, in some of the pieces that make up the spiral design. Against all historiographical premises, the runic symbols of America are observed in the cultural substrates of Araucanos, Tiahuanacotas, Guayakíes, Quimbayas, Incas, Kunas, Chupicuaros, Chumash, Anazasis, Navajos, Sinagua, Sac, Cherokies and Pima, among other groups.

Do these ideograms correspond to the ancient alphabet of the gods? The spiral symbol, from its earliest known representations in megalithism – a worldwide cultural phenomenon – is associated with the Sun as an expression of the birth-death-rebirth cycle and, therefore, with the forces of life.

It can be inferred, based on the calendrical function and its cyclical dimension expressed as a symbol of the spiral together with the objects that make it up, that this system has a magical-religious nature of great importance since it itself shelters and projects the cycle of life expressed precisely by the symbol of the spiral.

A vast horizon extends into the remotest past of South America, in which the presence of a civilizing substratum – the gods – burst forth to start the foundations of culture, that is, the development of mankind.

Top image: The Salar de Uyuni landscape in Bolivia. Source: subbotsky / Adobe Stock

By Rafael Videla Eissmann

References

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1995. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Primera parte. Tercera edición. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1995.

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1985. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Segunda parte. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1985.

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1996. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Tercera parte. Tercera edición. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1996.

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1994. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Cuarta parte. Volumen II: Guerra de Chupas ( Ca. 1553). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1994.

De Molina, Cristóbal, 1988. [ el cuzqueño ] Relación de las fábulas i ritos de los ingas (1575). Historia 16. Madrid, 1988.

De Murúa, (Fray) Martín 1946. Historia del origen y genealogía real de los reyes incas del Perú (1611-13). Biblioteca Missionalia Hispanica. Instituto Santo Toribio de Magrorejo. Madrid, 1946.

De Santacruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua, Joan, 1993. Relación de antigüedades deste Reyno del Pirú (1613). Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas. Cuzco, 1993.

Arellano López, Jorge, 2000. Arqueología de Lipes. Altiplano sur de Bolivia . Museo Jacinto Jijón y Caamaño – Pontificia Universidad Católica de Ecuador – Taraxacum, Washington D. C. Gráficas Rivadeneira.

Boman, Eric, 1908. Antiquités de la Région Andine de la République Argentine et du désert d’Atacama. Imprimerie Nationale. Libraire H. Le Soudier.

Cassasas Cantó, José M. 1977. Las poblaciones prehispánicas del altiplano perú-boliviano, puna y vertiente oriental andina. Separata de Aproximaciones a la etnohistoria del norte de Chile y tierras adyacentes . Conjunto de estudios publicados bajo la dirección del Doctor José María Cassasas. Universidad del Norte.

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1995. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Primera parte. Tercera edición. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1995.

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1985. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Segunda parte. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1985.

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1996. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Tercera parte. Tercera edición. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1996.

Cieza de León, Pedro. 1994. Crónica del Perú (1551-53). Cuarta parte. Volumen II: Guerra de Chupas ( Ca. 1553). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. Lima, 1994.

De Molina, Cristóbal, 1988. [ el cuzqueño ] Relación de las fábulas i ritos de los ingas (1575). Historia 16. Madrid, 1988.

De Murúa, (Fray) Martín 1946. Historia del origen y genealogía real de los reyes incas del Perú (1611-13). Biblioteca Missionalia Hispanica. Instituto Santo Toribio de Magrorejo. Madrid, 1946.

De Santacruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua, Joan, 1993. Relación de antigüedades deste Reyno del Pirú (1613). Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas. Cuzco, 1993.

Díaz Romero, Belisario, 1920. Ensayo de prehistoria americana. Tiahuanacu y la América primitiva (1904). Segunda edición refundida y mejorada. Arnó Hermanos.

Ibarra Grasso, Dick Edgar, 1980. Cosmogonía y mitología indígena americana. Editorial Kier.

Ibarra Grasso, Dick Edgar, 1982. Ciencia en Tiahuanacu y en el Incario (Astronomía y calendarios). Editorial Los Amigos del Libro.

Ibarra Grasso, Dick Edgar, 1982. Astronomía y sociología incaica. Editorial Los Amigos el Libro. La Paz-Cochabamba, 1982.

Videla Eissmann, Rafael, 2006. Signos rúnicos en la América del Sur. Ediciones Tierra Polar. Santiago de Chile, 2006.

Videla Eissmann, Rafael, 2008. Los Símbolos Sagrados de los Ingas. Ediciones Tierra Polar. Santiago de Chile, 2008.

Videla Eissmann, Rafael, 2011. Símbolos rúnicos en América. El regreso a la tierra ancestral . Prólogo de Vicente Pistilli. Editorial JG.

Videla Eissmann, Rafael , 2015. Símbolos rúnicos en América. El regreso a la tierra ancestral (2011). Prólogo de Vicente Pistilli.

Villamil de Rada, Emeterio, 1876. De la primitividad americana . Imprenta de Gutiérrez.

Villamil de Rada, Emeterio, 1888. La lengua de Adán y el hombre de Tiaguanaco (1888). Biblioteca Boliviana. Nº7. Publicación del Ministerio de Educación, Bellas Artes y Asuntos Indígenas. Imprenta Artística. La Paz, 1939.

Villamil de Rada, Emeterio, 1876. De la primitividad americana. El origen de los arios (1876). Edición y prólogo de Rafael Videla Eissmann. Colección bibliográfica La Historia Prohibida. Nº2. Ediciones Tierra Polar. Madrid, 2015.

Villamil de Rada, Emeterio, 1888. La lengua de Adán y el hombre de Tiaguanaco. La raíz de los idiomas indogermanos (1888). Edición y prólogo de Rafael Videla Eissmann. Colección bibliográfica La Historia Prohibida. Nº3. Ediciones Tierra Polar. Madrid, 2015.

Von Humboldt, Alexander, 2012. Vistas de las cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América (1810). Universidad Autónoma de Madrid – Marcial Pons Historia. Madrid, 2012.