Author’s Note: The allegation that the now-deposed Syrian Government systematically deployed chemical weapons against civilians during the 2011-2020 war is oft repeated widely by Western politicians, mainstream media, think tanks, and “regime change” activists. These claims have been supported, to varying degrees, by the world’s premier chemical weapons watchdog, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). In 2019, however, whistleblower scientists from within this organisation testified to the manipulation of the investigation of one of these alleged attacks, in order to reach a “pre-ordained conclusion” that the Syrian Government was responsible. In fact, the entire history of alleged chemical weapons (CW) incidents in Syria, dating back to as early as 2012, is controversial. This series explores the history of these allegations and sets out a preliminary case that the entire CW narrative is, in fact, a strategic deception designed to underpin a policy of “regime change” by delegitimating the Syrian Government.

Part 1 of this series examined the case of an alleged nerve agent attack in Homs in December 2012. This well-publicised alleged attack, complete with video of hospital scenes and testimonies from medics, was one of the most prominent of the early chemical weapons (CW) allegations and occurred in the context of the US Obama Administration, having declared a “red line” regarding CW use whereby, if crossed, overt US intervention would follow (I write overt because the US was already trying to overthrow the Syrian Government via a massive covert CIA operation called Timber Sycamore). The alleged nerve agent attack, was, however, rapidly discredited when it became apparent no such attack had occurred and that erroneous information had been channelled, in part, via a UK Government-funded propaganda operation.

It would not be long before the CW issue surfaced again. On 19 March 2013, there was an alleged chemical weapons attack launched on the town of Khan al-Assal, killing 16 Syrian soldiers. The day after, the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic addressed a letter to the President of the UN Security Council requesting a “specialized, impartial independent mission to investigate the alleged incident”.

On 21 March, the UN Secretary-General established the United Nations Mission. As William Van Wagenen documents in Creative Chaos: Inside the CIA War to Topple the Syrian Government (forthcoming in 2025), however, opposition forces quickly attempted to muddy the waters by blaming the alleged attack on the Syrian Government whilst, simultaneously and during the coming days, the UK, France, and Qatar relayed tit-for-tat allegations of CW use in Salquin (October 2012), Homs (December 2012), Darayya (March 2013) and Otaybah (March 2013).

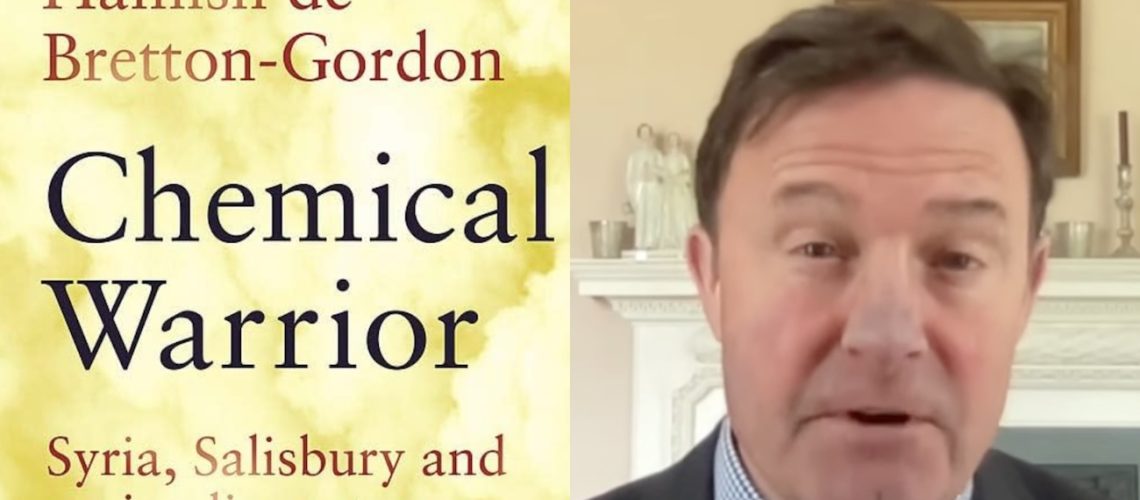

As plans were developed in order to initiate deployment of the United Nations Mission into Syria, so that the investigation requested by the Syrian Government could get underway, further alleged incidents occurred. It is at this stage that evidence of UK intelligence involvement with events surfaces again (As described in Part 1, the December 2012 alleged incident in Homs had been, at least in part, via UK organised and funded influence operations ARK and BASMA). Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a former British military officer, describes in his book Chemical Warrior how, after Khan al-Assal, he became involved in Syria when there was an alleged attack in Saraqib on 29 April 2013. He does not mention in his book, however, that he was also present following an alleged attack in Sheik Maqsood on 13 April. He certainly was present at Sheikh Maqsoud because, in a Wilton Park podcast, he subsequently described how he had worked alongside Times journalist Anthony Lloyd in order to obtain samples from this alleged incident. Later, UK media reports told of MI6 sample gathering operations during this period (see here and here) whilst British Prime Minister David Cameron referred to evidence provided by Porton Down defence laboratories and the UK’s Joint Intelligence Committee which ‘proved’ sarin was used at Otaybah and Sheikh Maqsoud.

Ultimately, when the United Nations Mission issued its joint report with the OPCW in late 2013, nothing much was to come of the flurry of attacks alleged by the US, UK, France and Qatar (see ‘Table One: CW Allegations and Joint UN-OPCW Investigation 2013’). Of the 11 accusations levelled at the Syrian Government, nine were not investigated on the grounds of “insufficient” or not “credible” information. These included, unsurprisingly, the 2012 Homs incident discussed in Part 1 of this series. Sheikh Maqsoud, at which Hamish de Bretton-Gordon was present, was investigated, but no corroborating evidence was found to support the allegation. Interestingly, this incident was reported to the UN Secretary-General via the US, rather than the British, and, as noted above, de Bretton-Gordon does not mention this incident in his book. Only the alleged incident at Saraqib was found to have evidence that “suggested” an attack had occurred. Furthermore, in a process that will become familiar when we examine alleged CW attacks from 2014 onwards, information regarding these alleged attacks had been funnelled by aligned groups such as the USAID-funded Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) and the France-based Union of Syrian Medical Relief Organisations (UOSSM) (see Creative Chaos). At the time, a Russian UN envoy made the following comment about the flurry of allegations:

We need to look into credible allegations … Unfortunately, I think what our western colleagues have been doing is trying to produce the maximum number of allegations with minimum credibility in an effort, one might think, to create maximum problems for arranging such investigation.

Conversely, all but one (three out of four) of the allegations issued by the Syrian government were found to have some level of supporting evidence with the original alleged attack at Khan al-Assal, which triggered the complaint to the UN, described in the joint UN-OPCW report as being “corroborated” by “credible information”.

Based, then, on a straightforwardly neutral reading of the 2013 UN-OPCW investigation results, most of the allegations made by the West and its ally Qatar were unsubstantiated whereas, at least to a degree, evidence was found to support the Syrian Government’s claims that its soldiers had been victims of CW attacks.

But then comes Ghouta.

Ghouta 2013

The UN-OPCW Mission initiated back in March was finally deployed to Damascus on the 18th of August 2013. It was headed by a Swedish academic Åke Sellström, with Canadian citizen Scott Cairns heading the OPCW component and Dr. Maurizio Barbeschi representing the WHO component. Within three days of their arrival, however, a rocket attack was launched into the Ghouta suburb of Damascus and which reportedly left hundreds of civilians dead from sarin gas. The UN-OPCW Mission was immediately refocused in order to investigate, in addition to the other earlier alleged incidents, the massive attack in Ghouta.

Predictably there were widespread calls from “regime change” lobbyists accusing the Syrian Government of being responsible for the attack and demanding the Obama Administration intervene militarily. In the US, a vote to authorise military action was organised, as was the case in the UK Parliament. The US Administration, however, backed away from overt military intervention whilst the UK Parliament voted against it. Meanwhile, the Russian Federation negotiated with the Syrian government to accede to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and, as a result, give up its arsenal of strategic chemical weapons. The immediate crisis surrounding threat of escalation was thus defused. But who was actually responsible for the Ghouta attack?

There are, in fact, a number of substantial reasons that lead us to conclude the attack was carried out by forces opposed to the Syrian Government. First, there is the matter of motive. It is unclear why the Syrian Government, having invited in the UN-OPCW mission in order to investigate an attack against its own soldiers, would suddenly decide to unleash a huge sarin gas attack right in front of the eyes, so to speak, of the investigation team who had just arrived in Damascus. Such action is made even more irrational by the fact that everyone was fully aware of Obama’s red line warning. There is simply no logical explanation for the Syrian Government to have launched such an attack. The motive for forces opposed to the Syrian Government, conversely, are clear. A massive and shocking atrocity that could be blamed on the Syrian Government would inevitably pressure the Obama administration to live up to its words about “red lines” and intervene in Syria against the government. Van Wagenen provides further circumstantial evidence for this “false flag” hypothesis in Creative Chaos, noting that prior to the Ghouta attack an “anti-Assad” operation, prepared with the help of US, Israeli and Jordanian intelligence, was in planning and involved a major assault on Damascus.

- (According to a Defense Department consultant, US intelligence has long known that al-Qaida experimented with chemical weapons and has a video of one of its gas experiments with dogs.) The DIA paper went on: ‘Previous IC [intelligence community] focus had been almost entirely on Syrian CW [chemical weapons] stockpiles; now we see ANF (Al-Nusra Front) attempting to make its own CW … Al-Nusrah Front’s relative freedom of operation within Syria leads us to assess the group’s CW aspirations will be difficult to disrupt in the future.’ The paper drew on classified intelligence from numerous agencies: ‘Turkey and Saudi-based chemical facilitators”, it said, “were attempting to obtain sarin precursors in bulk, tens of kilograms, likely for the anticipated large scale production effort in Syria.’

Remarkably, the identified launch site even matches up with a video released back in 2013 showing the rockets being launched by an AOG. And, at the same time, the painstaking

Rocket trajectories, impact points and launch areas from Ghouta Sarin Attack: Review of Open-Source Evidence by Michael Kobs, Chris Kabusk, and Adam Larson, 2021.

analysis provided in the review also confirms that the original UN-OPCW report contains a critical 30-degree measurement error which, back in 2013, allowed Human Rights Watch (HWR) and others to claim the computed trajectories prove the rockets were launched from a Syrian Arab Army military base. I asked Åke Sellström, the author of the UN-OPCW report, why this error had been made, and he was unable, over the course of several emails, to provide any kind of satisfactory response.

The Narrative Cements

Over time, the West and its allies have worked very hard to cement belief in Syrian Government guilt regarding Ghouta 2013. It remains a rallying call for all those who supported or were directly involved in the now, after 14 years, successful “regime change” war and, even today as massacres of minority groups are being reported, the narrative that “Assad gassed his own people” is used to whitewash this current round of murders now being carried out under the watch the extremist group brought to power in December 2024 by the West and its allies.

And yet, as we have seen, the evidentiary basis for the claim of Syrian Government guilt is paltry. The attack itself occurred firmly in the middle of an attempt by the Syrian Government to secure an investigation into a CW attack against its own soldiers at Khan al-Assal on 19 March 2013. A flurry of counteraccusation delivered by countries we know were sponsoring a major intelligence-led campaign to overthrow the Syrian Government came to little whilst, conversely, the claims of the Syrian Government were found to have support. And yet all of this was effectively buried by the massive event in Ghouta during August of 2013.

Although this attack has come to be understood as the fault of the Syrian Government, this looks very likely to be a myth. The striking absence of motive, the evidence that some of the victims were massacred, and forensic analysis of rocket trajectories all point toward actors other than the Syrian Government. Moreover, and as with Homs 2012, the paw prints of intelligence services are never far beneath the surface.

At the time, however, for those hoping that the Ghouta event could be used to force a massive escalation and overt intervention in Syria, led by the US, there was disappointment. The Obama administration backed away and, even worse for those seeking to exploit a CW narrative in order to promote “regime change”, Syria had acceded to the CWC and promised to surrender its entire strategic CW programme. Accusations of sarin use by the Syrian Government had become, therefore, difficult to make with any degree of plausibility.

As we shall see in Part 3, however, the CW narrative was to be revived in 2014 with a story line built around the Syrian Government, having surrendered its arsenal of advanced sarin strategic weapons in order to comply with the CWC, deciding to initiate a systematic campaign involving the dropping of chlorine gas cylinders on civilian populations.